Conservation News - July

Positive action for a biodiverse future

Wumindjika (Welcome)

A message from Jessica McKelson, General Manager Conservation

Image 1: Dedicated members of the bush stone curlew project team Senior Scientist, Dr Duncan Sutherland, General Manager of Conservation, Jessica McKelson and Australian National University PhD Candidate, Paula Wasiak.

Wildlife Wonders on Milawul – Pledge your support and get directly involved with our team

It’s been an incredible season at the Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre, and we’re excited to share some major milestones, and invite you to be part of what comes next.

Between January and April, our dedicated team responded to 420 wildlife calls, helping 40 different species, rehabilitating and releasing over 130 little penguins back to the wild. We also had a successfully Hoodie season with 13 hooded plover chicks fledging, adding to our long-term success for this threatened species.

One of our most exciting achievements this year was the historic reintroduction of 24 bush stone curlews to Phillip Island (Milawul) in April. These iconic birds haven’t been heard on the island since 1970. Now, with the removal of foxes, we're proud to play a leading role in bringing them back from the brink of extinction. To help protect them, we're asking everyone to please drive slowly on dimly lit roads around Rhyll and the Koala Conservation Reserve. We need to support this species and prevent vehicle strikes, one of the biggest threats.

We also have promising news from Cape Woolamai. Our upgraded drone technology has revealed natural regeneration of the Critically Endangered Crimson Berry plant. Seeing young plants take root again is a powerful sign that conservation efforts are working.

But we need your support and help!

- Volunteer with us and be a part of these achievements. We couldn’t do it without the 250 volunteers from our community! You can directly get involved with the rehabilitation efforts, bush stone curlew or even restoration works.

- Transform your home into a wildlife haven. Barb Martin Bushbank, native plant nursery has everything you need, including rare and threatened plants. Every plant you grow helps support our wonderful wildlife that we are privileged to share this Island with.

Together, we’re making a difference to support nature and important ecosystems on Milawul.

Marine Species

Threatened Species

Wildlife Management

Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre

Published Conservation News

Marine species

Little penguins

2024-25 penguin breeding season update

Kat McNamara, Research Officer

Breeding success of little penguins on Phillip Island (Milawul), is measured through regular monitoring at seven study sites across the Summerland Peninsula, where breeding pairs and their chick-rearing success are closely recorded. Success is measured as the number of chicks raised to fledging per pair, with a long-term average of one chick per breeding pair.

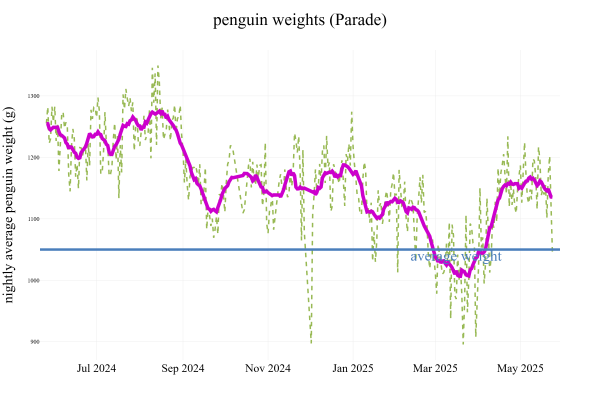

The 2024-25 breeding season began unusually early, with most penguin pairs laying eggs in July and August, nearly two months ahead of the long-term average. However, reduced adult weights recorded in September pointed to difficult conditions at sea. Many adults were forced to spend extended periods foraging, returning less frequently and with limited food for their chicks, which contributed to widespread first clutch failures. Fortunately, the early start to the season allowed time for successful second clutches making up for initial setbacks and resulting in an overall breeding success of 1.09 chicks per pair. This represents an average breeding success for the colony and is a strong outcome considering the challenging conditions earlier in the season.

Figure 1: The average weight of little penguins crossing the Penguin Parade Automated Penguin Monitoring System from July 2024 to May 2025. The solid blue line is the long-term weight average (1050 g), the dashed line is the nightly mean weight, and the pink line is the 14-day rolling weight average.

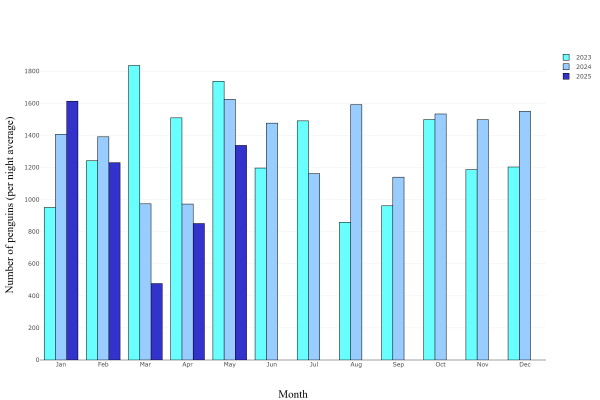

After breeding, little penguins undergo an annual catastrophic moult. This is a rapid, complete replacement of their feathers that takes about 17 days. This usually occurs between February and March, though some individuals start as early as January. This year, the moult peaked in March, leading to a drop in the number of penguins crossing the beach at the Penguin Parade.

Figure 2: The average number of penguins crossing the Penguin Parade beach each month from 2023 to 2025.

During the moult, little penguins stay on land and fast until their new feathers grow in as they can’t return to the ocean without waterproof plumage. To prepare, they spend two to five weeks at sea feeding heavily and nearly double their body weight. As new feathers grow beneath the old ones, penguins appear puffed up until the old feathers are fully pushed out.

Image 2: Moulting penguins under the Parade boardwalk.

Catherine Binns from University of Melbourne, has recently joined us as our latest Masters student, working on the project 'Health Assessment and Pathogen Screening in Little Penguins (Eudyptula minor) on Phillip Island, Victoria.' This two-year research project focuses on the active health monitoring and disease screening of the little penguin population at Summerlands. Active health assessments and disease screenings are vital for evaluating the current health status and identifying disease risks such as avian influenza and avian cholera, within the population. The aim is to establish blood reference ranges for the colony -, so we can understand what is normal and then we can track changes in the presence of disease.

Image 3: Masters student Catherine Binns and Megan Tucker, Senior Research Officer undertaking health assessment.

Australian fur seals

Entanglement study

Rebecca McIntosh, Senior Scientist

Jessalyn Taylor, PhD Candidate at Sydney School of Veterinary Science, demonstrated that loud motor vessel noise disrupted the normal behaviours of Australian fur seals at Seal Rocks and that recreational boats frequently move too close. Under the Marine Mammal regulations (2019), visitors to Seal Rocks are required to stay 60 m away from the seals unless on a permitted tour vessel and jet skis are defined as prohibited vessels and must stay 260 m away from Seal Rocks.

Our recently published paper 'Behavioural response of Australian fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus) to vessel noise during peak and off-peak human visitation' is available here.

We are very excited to announce that Jessalyn has been awarded her PhD after passing the rigorous international examination of her thesis. This is an amazing achievement, and we thank Jessalyn for her important conservation work and wish her success for her future endeavours.

Image 4: Jessalyn performing noise experiments at Seal Rocks.

Image 5: Australian fur seals at Sea Rocks

Threatened species

Threatened Species Report

Jessica McKelson, General Manager Conservation

To find out more about how the Nature Parks partners with the community on our ‘Island Haven’, download here.

Eastern barred bandicoots

Meagan Tucker, Senior Research Officer, Wildlife Team

In March 2025, the autumn Eastern barred bandicoot (EBB) trapping was undertaken across Churchill Island, Fishers Wetland and the Summerland Peninsula. Over three nights at Churchill Island, the Nature Parks staff and volunteers completed 63 captures of 44 individuals, 30% of which were caught for the first time. Fishers Wetland was also monitored, with 20 captures of 13 individuals, 31% of which were caught for the first time.

Over three nights at the Summerland Peninsula, the team made 50 captures of 35 individuals, 63% of which were seen for the first time. Body condition was predominantly average across all sites, with no pouch young observed, as is expected for this time of year.

Across these two trapping sessions volunteers contributed a massive 452 hours over seven days, assisting with trap setting, research assisting, EBB handling and free feeding. New volunteers were welcomed to the team, and dedicated long-term volunteers continued to receive training to develop their technical and animal handling skills.

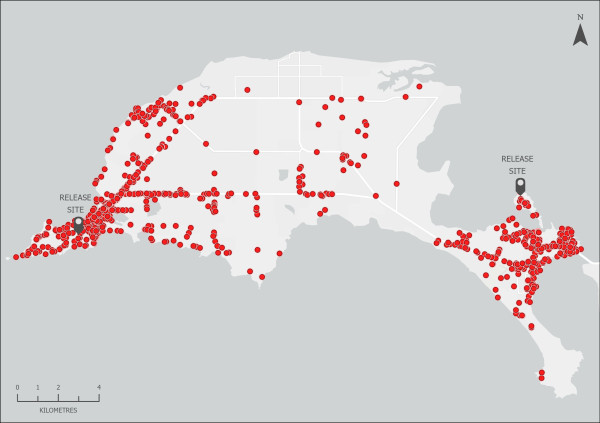

Bandicoots continue to slowly spread across Phillip Island (Milawul), with an increase in sightings around Cowes and Rhyll in the last six months. Community can contribute to tracking their spread by reporting sightings on our Bandicoot sightings portal.

Image 6: Eastern barred bandicoot distribution May 2025.

Bush stone-curlews

Kate Adams, Community Impact Manager

Bush stone-curlew health checks were conducted in February 2025 involving measuring body weight and condition, detection of external parasites, a visual assessment of general health, and a check of the leg bands and GPS devices. The birds have settled into two different zones around Oswin Roberts and Koala Conservation Reserve and were in good condition, indicating they are adapting to their new environment.

The trial release of the bush stone-curlews was deemed a great success with a 75% survival rate, one of the best outcomes for a trial of any reintroduction of the species.

Due to the success of the trial the project team moved to the next phase and released 24 additional bush stone-curlews in April 2025, in the hope the birds will establish a sustainable population on Phillip Island (Milawul), casting a lifeline to the species in Victoria.

This is part of a long-term recovery program in south-eastern Australia led by Odonata Foundation, the Nature Parks and The Australian National University.

Researchers will continue to monitor the birds’ movements with GPS trackers, undertake field health checks, and record their activities with acoustic recorders and remote cameras to reveal any threats to birds and their long-term recovery.

The community can play an important role in the success of the program by driving with care at dawn, dusk and night when the birds are most active, particularly in Sunderland Bay, Surf Beach, Sunset Strip, Silverleaves and Rhyll.

Report any bush stone-curlew sightings here or by emailing community@penguins.org.au

Image 7: Bush stone-curlew released on Phillip Island (Milawul)

Image 8: Dr Duncan Sutherland releasing a bush stone-curlew in an aviary after being fitted with a GPS harness.

Threatened flora – Crimson berry

Susan Spicer, Reserve Ranger, Reserve Team

With clear skies, low winds and ripe berries, autumn was the perfect time to use the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) to take another look at the crimson berry population growing below the light beacon at Cape Woolamai. This population is the largest on Phillip Island (Milawul) but assessing its size is difficult on vertical cliffs. In 2005, using binoculars from the top of the cliff, the population was surveyed at approximately 45 plants. In 2019, it was surveyed with a UAV and although this technique was promising and it could be seen that 45 was a conservative estimate, the resolution was not good enough to get a more accurate count. Now in 2025, with improved camera resolution from the UAV, we capture much better imagery to inform population assessment. A recent estimate of the population is in the range of 120-180 plants. There also appears to be a scattering of smaller younger plants lower down the slope, suggesting that our previous understanding that no recruitment was occurring is incorrect.

Image 9: Aerial view of crimson berry at Cape Woolamai captured during UAV survey.

Image 10: Craig Bester, Senior Vertebrate Pest Officer using a UAV to locate crimson berry.

Currant-wood conservation

The successful natural regeneration of an area excluded from rabbits and swamp wallabies in 2022 has inspired the Reserves team to create another similar zone within the threatened currant-wood habitat of Rhyll wetland. The team has constructed a 750 sqm enclosure that includes several mature trees of currant-wood, stinkwood thicket, and manna gum. However, the understorey and ground layer vegetation remain largely absent due to sustained browsing pressure by herbivores. By excluding herbivores from the area, it is expected that a broader range of native species, including currant-wood will be able to germinate, establish, and grow to maturity.

Image 11: Andrea Love, Environment Ranger constructing a regeneration coop.

Hooded plovers

Vivien Morris, Research Officer, Wildlife Team

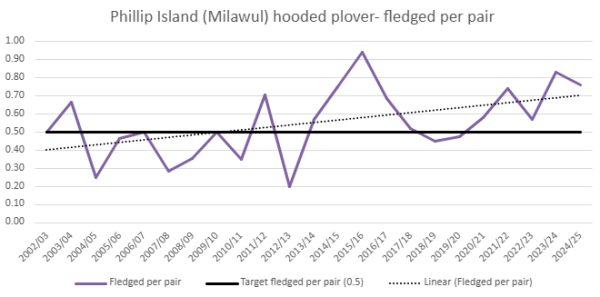

The 2024-25 breeding season was another strong year, with 13 Hooded plover chicks fledging from 17 breeding pairs. Breeding success is measured as the fledged per pair rate, which has been trending upwards over time. This season’s rate reached 0.76, well above the BirdLife Australia target of 0.5. Of the fledged chicks, 12 were banded with yellow leg flags engraved with individual letter-number combinations. Several of these birds have already been sighted off-island along the Bass Coast and Mornington beaches.

To investigate the causes of nest failure, eight wildlife cameras were installed facing active nests. Three of these monitored nest failures during the egg stage, and the footage confirmed that all three were lost to high tides washing away the eggs. However, a further 18 eggs failed for unknown reasons, highlighting the importance of continued camera monitoring to gather evidence and reduce uncertainty.

Our dedicated volunteers contributed 433 hours monitoring nesting birds, with an additional 54 hours supporting our quarterly Coastal Bird Surveys. Two interns, Charlotte Bond and Annie Preston from Deakin University, assisted across the season, maintaining nest cameras, beach monitoring, and helping to install wildlife refuges, contributing a combined total of 337 hours.

Figure 3: 2024-25 Hooded plover fledged per pair rate with trendline

Image 12: Hooded plover juvenile Yellow 5C at Summerland Beach

Wildlife management

Little penguins

Simon Heislers, Future-Proofing Little Penguins Project Coordinator, Reserves Team

Improving diversity and quality of habitat of exposed and degraded areas of the little penguin colony on the Summerland Peninsula is a priority for the Future-Proofing Little Penguins project. Little penguins are at increased risk of heat stress during summer heatwaves, particularly when sheltering in burrows during the hottest part of the day. The highest mortality rates occur in exposed or degraded habitats, where there is little natural protection from the sun.

Heat waves are becoming more frequent with climate change, and a basic goal of the project is to increase the extent of shade by establishing more trees and shrubs and improving habitat quality and diversity in exposed and degraded areas. This ultimately cools the environment and improves the resilience of the little penguin colony.

The Summerland Peninsula is a stressful environment for plants to establish and grow. Vegetation is strongly influenced by a variety of variables including climate, soil type, animal colonies, animal browsing and people (mostly historic land management impacts). The survival rate after the first critical six months of the 5,000 native, fire-retardant herbaceous plants and trees and shrubs planted last winter was approximately 55% (for guarded plants). Survival was greater for herbaceous (low growing, non-woody) plants than trees and shrubs (~60% compared with 45%) but rates varied significantly across the landscape (at small, localised scales) and seasonally (with changes in climate and browsing impacts).

Browsing pressure and planting success

Browsing animals, such as swamp wallabies and Cape Barren geese, have had a significant impact on seedling survival, including within the green firebreak areas. The most obvious damage occurred within the first week of planting, when approximately half of all tree and shrub mortality recorded at six months was caused by browsing. Seedlings were either eaten directly from the guards or pulled out of the ground. While this effect is commonly seen in revegetation projects, the strong impact observed on Summerland Peninsula highlights the need to invest in guarding systems from the moment of planting, as well as exploring other strategies to support successful establishment and growth.

Habitat planting trials

Habitat plantings include a number of trials aimed at improving outcomes for conservation plantings. These trials are investigating whether planting in association with natural or existing landscape features, such as under trees, among other plants, or within dense native vegetation, can improve seedling survival. Other trials test whether clustered plantings (compared to mass plantings) and summer watering during dry periods can also offer benefits. Although these trials are in their early stages, they are already showing positive results. For example, we’ve found that planting seedlings under or in direct contact with existing vegetation, such as native grasses, thistles, trees, or kangaroo apples, greatly improves survival and growth. Interestingly, the specific type of vegetation appears less important than the presence of cover itself, a finding that offers valuable insight into improving conservation planting success.

Image 13: (left) Closed foreground and open background clustered plantings in exposed, degraded little penguin habitat on Summerland Peninsula south coast. (right) Top view of closed cluster showing good success with boobialla, bower spinach and noon-flower thriving.

Koalas

Lachlan Sipthorp, Senior Ranger Wildlife Team

At the end of 2024, wildlife rangers at the Koala Conservation Reserve began harvesting material for new koala railing infrastructure for the viewing areas. Railings were cut at one of Westernport Water’s plantations along with leaves for feed. The woodland boardwalk koala rails were re-worked to provide koalas easy access to new supplementary feed stations and existing nearby habitat.

Volunteers and rangers worked together to tidy up the Bluegum Koala Trail and soft release enclosures. Fresh mulch was chipped out of the deadwood and fallen debris and reapplied to pathways and trees within the enclosure to improve overall tree health. In addition, some trees were banded to allow for regrowth and protection from possum browsing pressures.

At the Reserve, artificial tree hollows were installed in the woodland area for kookaburras and kingfishers to nest in and some of the hollows were active which provided great views of kookaburra chicks for visitors.

Our latest male joey was named Toddles via a Facebook community naming opportunity. We hope to have another successful breeding season later in the year.

Image 14: Environment Ranger, Zoe Kellett holding Toddles the male joey during an annual health check.

Cape Barren Goose Research

Vinent Knowles, PhD Candidate University of Melbourne

As part of a PhD project based at the University of Melbourne, 100 Cape Barren geese were fitted with tracking devices integrated into plastic neck collars across Phillip Island (Milawul) during the second half of 2024. Of the geese tagged, 38 left the island during the non-breeding season (December to April), with all but seven returning by 1 May 2025.

Twenty-two Cape Barren geese moved to the Bass Coast between Jam Jerrup and San Remo, seven moved to Venus Bay and Tarwin Lower, four moved to the Yanakie Isthmus, near Wilsons Promontory and three flew to the Mornington Peninsula around Tyabb and Pearcedale.

As of 1 May 2025, two Cape Barren geese appeared to have moved permanently to French Island. Geese that left the island included both breeding and non-breeding adults, as well as juveniles. On Phillip Island (Milawul), Cape Barren geese have also been mobile, leaving their breeding and moulting sites at the Summerland Peninsula, venturing to various paddocks on the island. However, some have also remained in their territories year-round, with very little movement from their initial capture site.

The data collected has shown significant variation in movements of Cape Barren geese and for the first time has shown that geese from Phillip Island (Milawul) can complete large movements in the non-breeding period, filling important gaps on this population's movement ecology.

As well as tracking devices, 50 geese, primarily from the Summerland Peninsula, have been banded with plastic neck collars. These individuals will contribute to our understanding of nesting and breeding over the next two years. These collars have a unique two letter code engraved in them, for example: “HD” or “EK.” We encourage members of the community to report sighting and breeding activity of these Cape Barren geese to Vincent Knowles via email.

Image 15: Cape Barren goose wearing a tracking device

Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre

Brittany Pullin, Senior Wildlife Welfare Officer & Rosie Stott, Wildlife Ranger, Wildlife Team

From wallabies to wedgies, we have been busy here at the Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre. From January through to April we had 420 wildlife calls made up of 40 species with little penguins taking the spotlight at nearly one third of the calls and over 130 little penguins being rescued over the 4-month period. Alongside little penguins we saw pelicans, gannets, gulls, echidnas, Eastern barred bandicoots, wedge-tailed eagles and many more species through the centre.

Now as temperatures are dropping, and wildlife activity across the island slows, we are expecting a quieter period. Despite the shift in temperature, the island is still relatively dry, and you can continue to help wildlife by leaving water out. If you are concerned about an animal, you can contact Wildlife Victoria’s Emergency Response Service 24/7 on 03 8400 7300.

Success stories

The busy summer season brought an influx of little penguin chicks and, while we thankfully avoided any large-scale mortality events, we still received several heat-stressed little penguins over the warmer months. The end of breeding season then brought a wave of emaciated little penguin chicks, moulting their downy plumage.

Image 16: Little penguin chick moulting downy plumage.

We also had five juvenile gannets transferred to us for rehabilitation, from the Melbourne Zoo's Marine Response Unit. These birds often require being taught to eat fish on their own, eventually being able to ‘catch’ fish when it is tossed into the sea bird pool at the rehabilitation centre.

Image 17: A gannet swimming in the sea bird pool at the Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre.

We need to ensure that gannets are waterproof and help them develop their muscles for flight. To do this we encourage suitable preening behaviours by swimming them in a pool to stimulate bathing and also by running an overhead sprinkler system. The sprinklers help act as light rain would, encouraging wing flapping. When they are ready for release, we choose days with strong winds. We take them to a suitable launch site and let them decide when they are ready to take off. Sometimes it takes more than one attempt before the birds choose to take off and fly away. On average these birds have been in care for three to four weeks before they are ready for release.

Image 18: Australasian gannet considering takeoff.

All five juvenile Australasian gannets have now been successfully rehabilitated and released. With the centre so busy, we’d like to shine a light on our incredible and dedicated wildlife rehabilitation volunteers. They have already contributed over 100 hours this year. Also, thanks to the Wildlife Victoria volunteers who attend daily calls, their support is invaluable. We simply couldn’t do this work without them!

Image 19: Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre volunteers releasing little penguins on Summerland Beach

Shearwater Patrols

April to May is the annual short-tailed shearwater fledging season when chicks begin their approximately 8,000 km journey north towards the Aleutian Islands via Japan. For a 3-week period, the Nature Parks Conservation team works tirelessly to help rescue birds that have ended up on our roads. A total of 111 hours was spent by the team patrolling the roads and setting up signage to warn visitors of the presence of shearwaters. Lights on the bridge were turned off for nine nights and Summerland Peninsula road lights were turned off from the 21 April-10 May to assist the birds begin their migratory flight.

Although strong winds were not recorded over Phillip Island (Milawul) over this period, south-west winds caused some problems for the fledging birds as these light winds pushed them back on land and towards roads. A total of 138 shearwater fledglings were rescued and returned to the colony during patrols over a three-week period, with another 23 rescued and released through the Wildlife Rehabilitation Centre. Hot spots for the patrols included Forrest Caves and Surf Beach, where shearwaters were found deceased. In these areas the colony is close to a road with busy traffic. While at Cape Woolamai, where the colony is close to roads, but with far less traffic, more shearwaters were rescued.

Image 20: Short-tailed shearwater patrol

Publications

Breidahl, A. J., Lynch, M., Sutherland, D. R., Traub, R., and Hufschmid, J. (2025). A multi-modal approach to enhance Toxoplasma gondii detection in the Australian landscape. Wildlife Research 52.

doi: 10.1071/wr23091.

Bruce, T., Amir, Z., Sutherland, D. et al. (2025). Large-scale and long-term wildlife research and monitoring using camera traps: a continental synthesis. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.13152

Hee, M., Mathieson, A. & Connor, S. 2025. Health impacts of the 2019–2020 Australian “Black Summer” bushfires: smoke-related asthma emergency department presentations in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, International Journal of Environmental Health Research,

https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2025.2494734

Joly, N., Chiaradia, A., Georges, JY. et al. Individual variability in the phenology of an asynchronous penguin species induces consequences on breeding and carry-over effects. Oecologia 207, 16 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-024-05644-6

Lynch, M., Liyanage, K. L. D. T. D., Stent, A., Sutherland, D. R., Coetsee, A., Adriaanse, K., Jabbar, A., and Hufschmid, J. (in press). The use of a multimodal approach to assess the Impact of Toxoplasma gondii in endangered eastern barred bandicoots (Perameles gunnii). Journal of Wildlife Diseases

Podsosonnaya, M., Schreider, M. J., & Schreider, S. (2025). Modeling Estuarine Algal Bloom Dynamics with Satellite Data and Spectral Index-Based Classification. Hydrology, 12(6), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology12060130

Simpson, M. D., A. L. Dickerson, A. Chiaradia, L. Davis and R. D. Reina (2025). Divorce Rates Better Predict Population-Level Reproductive Success in Little Penguins Than Foraging Behaviour or Environmental Factors. Ecology and Evolution 15(1): e70787.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.70787

Yaney-Keller, A., McIntosh, R.R., Clarke, R.H., and R.D. Reina (2025). Closing the air gap: the use of drones for studying wildlife ecophysiology. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.13181