Mandeville Road from the north end looking south, before (above) and after (below) completion of mulching and slashing operations of the firebreak area.

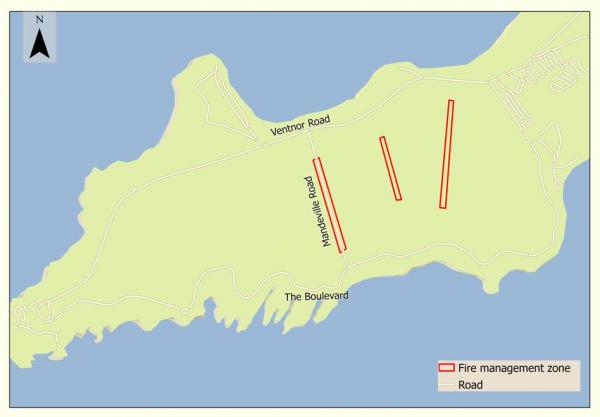

During May 2023 Phillip Island Nature Parks staff and contractors completed a mechanical fuel reduction/weed control operation within the Summerland Peninsula as part of the first stage of field activities of the Future Proofing Little Penguins from Bushfire project.

The aim of this project is to create a series of three parallel ‘green’ firebreaks that run north-south across the Peninsula. The three firebreaks are situated along Mandeville Road and two management tracks east of Mandeville Road (formerly known as Solent Avenue and Portslade Road). These firebreaks will help reduce the risk of bushfire from impacting the Peninsula including the penguin colony while also providing habitat for penguins and other wildlife.

Recently completed operations resulted in the effective removal of the woody fuel load from the firebreak areas and specifically thickets of Swamp Paperbark (Melaleuca ericifolia) that dominates extensive areas of the interior of the Peninsula. Swamp Paperbark is indigenous to the Summerland Peninsula and is an important component of the vegetation, but as with some other species it poses a significant fire risk in some situations and needs to be managed.

Great care was taken during mulching and slashing operations to ensure that wildlife were not harmed and that burrowing animals and their burrows/nestboxes were protected. This involved conducting daily fauna surveys with a special focus on looking for animals in burrows, spotting for animals during operations, and protecting ‘high risk’ areas (where animals were identified) from mechanical operations.

The next stage of operations will occur during Spring later this year when native, mostly indigenous, fire wise plant species will be planted within the firebreak areas. These species will generally be low growing, herbaceous (non-woody), and fire resistant/retardant, but have been selected to provide for the habitat requirements of penguins and other wildlife and to promote biodiversity.

The value of scientific monitoring in understanding ecology and driving conservation actions

Six months have passed since the green firebreaks were established on the Summerland Peninsula which is a critical period for the establishment of plants. The 15,000 indigenous, fire-retardant plants that were planted have been left to grow, but they haven’t been growing in isolation. From the moment they left the nursery and were planted they became part of a wilder, more complex, and stressful ecosystem where their survival and growth are strongly dependent on a wide range of climatic, environmental, and ecological conditions.

Survival assessments of plantings across the three firebreaks show that three months after planting average survival for plants with guards was quite high at 85%, but this dropped to 53% at six months (post summer). While this may not sound very high (and it isn’t), the value of guarding in improving survival at establishment is clear when comparing these values to survival rates of plants planted without guards (27% at three months and 13% at six months). Based on these values, guarding improves survival rates by three to four times during establishment. While this result is interesting, the data collected from survival assessments does not provide any detail as to what may be influencing success, but the fenced browsing exclusion trial does.

The browsing exclusion trial is a feature of the ‘Future-Proofing Little Penguins’ project and newly established green firebreaks. It exists as a series of fenced and unfenced plots installed at the time of planting and was designed to allow assessment of the impact that browsing animals, including swamp wallabies, Cape Barren geese, brushtail possums and rabbits, have on the conservation plantings, and the environment more generally. Animal browsers can significantly influence the type and form of vegetation that grows, as shown on the Summerland Peninsula. But this impact has not been previously measured in any meaningful way on the peninsula.

Image: Cape Barren Goose on Mandeville Road.

The fences effectively excluded all large animal browsers wallabies, geese, rabbits, and possums) on the Mandeville Road firebreak, and after six months survival was 84% (averaged) in the fenced browsing exclusion plots versus 67% (averaged) in the unfenced (control) plots. This result suggests that browsers have had a significant impact on survival (accounting for approx. 17% of the difference in survival between fenced and unfenced plots) although other factors (including climatic and environmental) have had an equally big impact to date (accounting for 16% of loss of plants in the fenced plots).

Surviving plants in fenced plots were generally healthier and had more vigour than those outside with 38% of plants growing out beyond their plant guards versus 7% in unfenced plots, many of which showed clear signs of having been browsed.

Browsers have had a significant negative impact on the integrity of plant guards in unfenced areas, crushing, tearing, and pushing guards over (31% of all guards in unfenced plots were impacted by browsers). This not only exposes plants to browsing but reduces any positive benefit the guards provide for improving microclimate and boosting growth.

A significant number (19 total) of naturally germinating seedlings of native shrub / trees (Boobialla and coast wattle) were recorded in fenced plots while none were recorded from unfenced plots. Germinants of native shrub and tree species are very rarely observed in the landscape and generally don’t grow to mature size. Establishment of more shrubs and trees and the provision of shadier, cooler penguin habitat is a focus of the ‘Future-Proofing Little Penguins’ project and this result is valuable for future conservation planning.

While fencing and excluding browsers appears to be providing benefits, excluding browsers can impose other stresses on plants and cause changes to occur in the environment that require further management action to redress.

At the time of planting (and installation of fenced browsing plots, the firebreaks had been slashed and cleared of all vegetation and most notably dense, woody, swamp paperbark, but a substantial amount of natural regeneration has occurred since. After six months fenced exclusion plots have almost twice as much total vegetation cover as unfenced plots (70-80% average cover versus 40-50%). All plots had a similar amount of cover of grass and herbaceous plant species but swamp paperbark (20-60% cover, 30-40cm tall) was a dominant component of fenced plots while it was practically absent (<1% cover, <1cm tall) in surrounding (unfenced) areas. This result shows how much impact browsers are having on the environment and vegetation generally, that they are effectively prohibiting swamp paperbark from regenerating in the firebreaks and the peninsula more broadly, and actively browsing out many other species including all other shrub and tree species and many groundcovers.

So, while installing fences may improve plant survival and growth and potentially provide other benefits for revegetation projects such as improving biodiversity, they may also cause significant and unintended changes in vegetation requiring significant additional resource to control. Striking the right balance between control and taking action is critical to achieving successful conservation outcomes and knowing what (and how much) to control to achieve the desired outcome is key.

The browsing exclusion trial is only just starting to provide an insight into the effects of browsers on the vegetation and of the broader ecological dynamics of the peninsula and more will be learned in the years to come. Ultimately the information gained will help inform future conservation actions and lead to better and more sustainable conservation outcomes.

Image: Mandeville Road firebreak fenced browser exclusion plot 6+ months after planting.